- Home

- Christian Hill

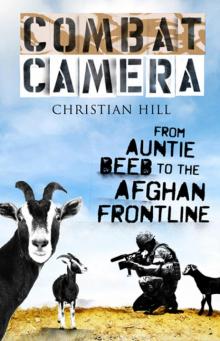

Combat Camera

Combat Camera Read online

COMBAT CAMERA

COMBAT CAMERA

From Auntie Beeb to

the Afghan Front Line

CHRISTIAN HILL

ALMA BOOKS LTD

London House

243–253 Lower Mortlake Road

Richmond

Surrey TW9 2LL

United Kingdom

www.almabooks.com

First published by Alma Books Limited in 2014

Copyright © Christian Hill, 2014

Christian Hill asserts his moral right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

ISBN: 978-1-84688-320-0

eBook ISBN: 978-1-84688-325-5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher.

Combat Camera

Author’s Note

PART ONE

The Fighting Season

The Wasted Decade

Home Fires

The Combat Camera Team

PART TWO

Inside the Wire

Shahzad

Making Things Look Better

War and Peace

Two-Headed Beasts

Shorabak

OBL Dead

Dogs of War

Embeds

Omid Haft

PART THREE

The Retreat to Kabul

Theatre Realities

Death or Glory

Cameraman Down

Wear Your Uniform to Work

Outside the Wires

A Hazardous Environment

Last Legs

Epilogue

APPENDIX 1

Field Reports and Significant Acts

APPENDIX 2

Afghanistan Fatality and Casualty Tables

MoD Definitions of “Very Seriously Injured” and “Seriously Injured”

Glossary

Acknowledgements

To my family

COMBAT CAMERA

Author’s Note

I kept a daily journal throughout my tour of Afghanistan. All the events in this book happened as described. For reasons of privacy or at their own request, the names and identifying details of some individuals have been changed.

PART ONE

The Fighting Season

At just after 7 a.m. on 19th May 2011, the Indirect Fire alarm started to sound at Camp Bastion. I heard the siren as I lay in bed, burrowing my face into my two pillows. Whenever I stayed at Bastion, I liked to make the most of its comforts – my bed also came with a duvet and a surprisingly firm, unstained mattress. Compared to life on the patrol bases, it was like staying at the Ritz.

The siren continued to wail across camp, but nobody stirred inside our air-conditioned tent. It was a drill, quite obviously. I pulled my duvet up over my head, trying to get back to the Caribbean. I’d been dreaming about an ex-girlfriend, the two of us lying on a beach in Montego Bay, such a long way from Bastion and its tedious routines.

The first explosion hit about a second later. It wasn’t that loud, but it was still loud enough to make me jump out of bed.

“Fuck,” I said.

Dougie had sprung out of his bed at the same time. He wasn’t the most agile of guys, so it had to be serious.

“IDF,” I heard him say, just in time for the second explosion, this one definitely closer.

I grabbed my pistol – for some reason – and ran from our tent to the Joint Media Operations Centre in my T-shirt and shorts. Dougie hurried in about ninety seconds later, fully dressed in his helmet and body armour – the correct response.

“Are we safer in here?” I asked him.

“I guess so,” he said. “We should be lying on the floor, though.”

We looked at each other for a long moment, two soldiers standing in a flimsy, prefabricated office. The drill in these circumstances was to lie face down on the floor with your hands by your sides, an ungainly position at the best of times. Our fear of discomfort and embarrassment outweighed any concerns about getting blown up, so we just stood there like idiots.

Faulkner walked in, the floor creaking beneath him. He was unfeasibly tall for an old pilot, and he looked even bigger in his helmet and body armour. I began to feel very underdressed.

“Christian, get round, make sure everybody is up,” he said. “Helmets and body armour all round.”

The all-clear siren rang out a short time later. Headquarters wasn’t yielding a great deal of information about the incident – a few lines appeared on Ops Watch* at 07.40, describing “two blasts at Bastion” – but that was it. We all went off for breakfast, then returned to the office for another day of emails and phone calls, our helmets and body armour still close to hand, propped up against our desks.

Details of incidents at other Helmand bases flashed up on Ops Watch throughout the day, but we didn’t realize the full scale of the offensive until Faulkner’s brief in the office that evening.

“It’s been one of the busiest days in Helmand for a long time,” he said, a stack of printouts on his desk. “Over thirty coordinated IDF attacks on bases across the province.”

He went through the details. Considering the number of incidents, the damage assessment was remarkably low.

“A couple of insurgents were killed, and some civilians died. We just had a head injury.”

The attack on Bastion – the first of its kind since November 2009 – had seen two 107-mm rockets fired into the camp from rails* found seven kilometres away. One had come down on the outskirts of camp without damaging anything, while the other had landed in a vehicle yard a short walk from our office. A US Marine had to be treated for “splatter” to his back, but otherwise we were spared the casualties.

Faulkner pointed to a sketch on the whiteboard behind him. “We found another firing point with five rails, but all those rockets missed us.” He’d drawn five lines going just wide of a blue squiggle that represented Camp Bastion. “We got lucky, to be fair. It could’ve been a lot worse.”

I sat there listening to him, trying to remember why I’d come out here in the first place. It was a long way from the comforting world of BBC local radio, warm and fuzzy with its homely procession of shallow councillors, miserable trade unionists and confused pensioners. Quiet desperation had been enough to unseat me from my news desk in Leicester, tipping me out into the middle of the Afghan desert. Like thousands of actual proper soldiers before me, staggered throughout the last decade, I had traded boredom for potential horror. In less than a week I was due out on the first big operation of the summer, highlighting the efforts of British troops in the latest round of the war. A lot of the Taliban would get killed, and some of us would get shot and blown up too.

“If this isn’t the start of the fighting season, I don’t know what is,” Faulkner said. “We can expect more attacks, more casualties and more vigils.”

It was perfect timing for our incoming celebrity guest. The soap star turned war reporter Ross Kemp was due to land at Bastion in a matter of hours, one of a gaggle of embeds touching down after midnight. They all had to be picked up from the flight line, briefed, accommodated and generally looked after. It was going to be a busy week for my colleagues in the office.

I met Ross the following morning. My team were filming and photographing his Tiger Aspect crew on their day-long induc

tion package, recording for the military’s archives their movements around Bastion’s mock-up of an Afghan village. The mud compounds offered no respite from the heat and dust, so in between the sweaty tutorials on first aid and IED awareness, we took an early lunch in the shade of a nearby hangar. The food was standard Bastion training fare: boxes of soul-destroying sausage rolls, bags of peanuts and countless fruit-and-raisin bars.

“This food is great,” said Ross, to no one in particular.

“You’ve obviously not tried the sausage rolls,” I said.

“I like these ones.” He started eating a fruit-and-raisin bar.

“They’re great, not like the food we had once in Musa Qala last time I was out here. We were tabbing all night, going for hours. They were dropping two-hundred-pound bombs all around us, guys were getting hit, two guys got broken legs. It was unbelievable.”

He continued in this manner for another two minutes, shoving food into his mouth the whole time, telling me all about the hardships he’d faced in Musa Qala. I wasn’t sure where the “two-hundred-pound bombs” had come from, but he sounded genuine enough.

“We finally got to the patrol base, just in time for breakfast, absolutely starving, and you know what they served us? One rasher of bacon and some powdered egg.”

I didn’t quite know how to respond to this anecdote. I had no war stories of my own, but clearly with Ross around, I didn’t need any. I’d watched his DVD box set before coming out here, and seen plenty of footage of him on his hands and knees in Green Zone irrigation ditches, grimacing into the camera as the bullets whizzed overhead. That was his money shot, the reporter under fire, right in the heart of the battle. It wasn’t enough for him just to interview the soldiers and tag along at the back of the patrol. He had to be seen to be in the firing line, front and centre for the ratings war.

I was different. I didn’t need to crouch down in front of the camera, delivering breathless reports on the latest fighting. My presence on film was not required. I interviewed the soldiers, and I looked after my team on the ground, but that was it. My questions would always be cut from the final edit, and if I appeared in any photographs, they would always be deleted. I was the army’s voiceless, invisible correspondent, right on the edge of the action, just outside the shot. Nobody wanted me in the picture, least of all my colleagues in the British media.

I left Ross to his fruit-and-raisin bars and returned to the office, where my new friend Mikkel was sitting at my desk, holding his disturbingly skull-like head in his hands, the very image of a tormented Dane.

“There has been a problem with next week’s operation,” he said.

I wondered for a second whether he meant the operation had been cancelled. We were supposed to be joining 1 Rifles and 42 Commando on a heli-insertion into Nahr-e Saraj. Mikkel’s responsibilities extended to booking our seats on one of the helicopters. He mentored our counterparts in the newly formed Afghan Combat Camera Team. They were supposed to be joining us on the operation, learning from us, watching how it was done.

“What’s wrong?” I said.

“All the helicopters are full,” he said. “You’ll have to go in on foot.”

“Please tell me you’re joking, Mikkel.”

He ran a bony hand over what little remained of his hair. “At least you’ll get some better footage,” he said. “There’ll be more action out on the ground.”

This was kind of true, but it was also bullshit. The heli-insertion would’ve provided us with some great footage. Instead, we’d be inching our way through the IED-riddled fields of Nahr-e Saraj on foot, very probably getting shot at.

“Where are your guys going to be?” I asked him.

“I don’t think they’re coming.”

The change of plan meant we’d now be deploying earlier than expected, flying out to Patrol Base 5 to meet up with two companies from the Afghan National Army. They were patrolling from the base via Checkpoint Sarhad to the Nahr-e Bughra canal, a distance of some three and a half kilometres. That didn’t sound like much, but it would take at least two days. The plan was to clear the area of insurgents, making it safe for the Royal Engineers to build a bridge over the canal.

The plans changed again the next morning, and kept changing over the next two days. We were back on the heli-insertion, then we weren’t. We were back with the Afghan National Army, then we weren’t. We were driving in with the Royal Engineers on a road move, then we weren’t. Tension and uncertainty ruled the day, as it always did in the run-up to an operation. Surrounded by the comforts of Bastion, we distracted ourselves as best we could, killing time in the gym and the canteen and the coffee shop.

On the night of 23rd May, I was in my tent checking over my kit – we were back on with the Afghans, flying out to Patrol Base 5 the following morning – when the news came through that a British soldier had just been seriously injured in Nahr-e Saraj. Against my better judgement, I left my kit and went over to the office to get some more details.

It was quiet that night. Only Dougie was at his desk, going through the latest field report on Ops Watch.

“Bad news,” he said.

I stood behind him and read the report over his shoulder. A foot patrol out of Patrol Base 5 had struck an IED a few hundred metres from Checkpoint Sarhad. The British soldier caught in the blast had now died of his wounds. An Afghan interpreter had also been hurt – he’d been flown to Bastion with a shrapnel wound to his neck.

“Sarhad?” Dougie said. “That’s where you’re going, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” I said. “I better get back to my kit.”

I left the office and went back to my tent, trying to think about my kit, trying not to think about the soldier’s family back in the UK, right now being told about his death, the chaplain and the officer standing on the doorstep, heads bowed. It was the worst way to prepare for an operation, running this kind of stuff through your head, but I’d always had a stupid, flighty imagination, and I couldn’t help myself. Inevitably I would start to think about my own family, my parents and my brother and my sister, all of them sitting around the dinner table at home, all of them hearing the knock at the door.

I really did not want to go on this operation. If I could’ve seen out the rest of my tour at Bastion, that would’ve suited me just fine. Yes, I’d volunteered for the Combat Camera Team, but that didn’t mean I wanted to get myself killed. Like most of my career decisions to date, I didn’t know what I wanted, but I knew it wasn’t a grisly demise in this shithole.

I’d read enough field reports on Ops Watch to know everything I needed to know about the vast unpleasantness of combat. It was all anybody needed to know. You didn’t need Ross Kemp to guide you through the horror, and you certainly didn’t need the army’s own-brand footage.

You just needed to read the field reports.

*

Like a number of offices at Bastion, the JMOC had an Operations Watch terminal. A laptop hosting a near-real-time feed of incidents taking place across theatre, it reproduced reports sent directly from the field.

*

Insurgents would fire rockets off lengths of metal rail, driven into the ground at an angle.

The Wasted Decade

I never had a burning desire to join the army – I just liked the idea of it. Notions of duty and honour appealed to the romantic idiot in me. I’d served in the cadets at school, and then the Officer Training Corps at university, so the grown-up army felt reassuringly familiar, like another warming dose of higher education. I’d graduated in the summer of 1995 with a half-baked degree in psychology, still unsure about my calling in life. I enjoyed writing, I knew that much, but that had yet to translate into an interest in journalism. Reluctant to pursue a career of any kind, I took the decision to become an army officer: my plan was to coast along on the Queen’s shilling for three years, and then start worrying about a normal job.

Not unpredictably, the grown-up army put something of a rocket up my arse. Despite all my years in the ca

dets and the OTC, I was not prepared for Sandhurst’s opening salvo of polishing, ironing and square-bashing. Throughout our first term we did nothing but drill for hours on end, marching up and down to the screams of impossible-to-please colour sergeants. At night we’d limp back to our little rooms in Old College and surrender to our wardrobes, toiling over our shirts and trousers and boots for the dreaded inspections at dawn.

It got better, thankfully. The more we learnt about soldiering, the more the colour sergeants treated us like grown-ups. We traded the Academy grounds for the great outdoors, learning how to fight in the ditches of Norfolk and the mountains of Wales. It was still difficult and unpleasant, but at least we were starting to feel like men, as opposed to errant schoolboys.

I had no desire to become a poor bloody infantryman, but I could still see the attraction in doing something toothy. When the time came to choose our regiments, I put my name down for the Royal Artillery. If I’m being honest, it was the concept of fighting at a distance that appealed to me – the idea that you could do your bit on the battlefield, but from a good ten miles away.

Happily, the Royal Artillery accepted me, so when I finally made it out of Sandhurst, I had a place waiting for me on the Young Officers’ course at Larkhill. It was the home of the Royal School of Artillery, a place where second lieutenants could while away five months on a lot of cheap booze and some easygoing lessons in gunnery.

It was a wonderful period of my life, with nothing worth documenting for serious purposes – suffice to say that I was happy and content. Perhaps riding on a wave of good karma, I landed a surprise posting to one of the better Gunner units – 3rd Regiment Royal Horse Artillery.

My career at 3 RHA wasn’t entirely distinguished, but then it wasn’t a disaster either. It was so-so. I gained a reputation for sleeping a lot, which was understandable, given the nature of my deployments.

I spent four months in Bosnia, serving as an operations officer in a small town called Glamoč in the spring of 1999. Theoretically, it was an interesting time to be in the Balkans – NATO was attacking Belgrade, trying to stop a massacre in Kosovo – but you wouldn’t have known that where we were. Glamoč was populated by Bosnian Croats, all of whom were on their best behaviour. They had no beef with NATO, naturally – we were bombing the Serbs.

Combat Camera

Combat Camera